Did you know bats can catch over 1,000 insects in a single hour? Most people only see bats as scary creatures of the night.

But there’s so much more to these flying mammals. The life cycle of a bat includes some truly interesting facts that many folks don’t know about.

Want to learn what makes these night flyers so special? This article shows the complete life cycle of a bat from birth to adulthood.

Understanding Nature’s Nighttime Navigator

Bats are the only mammals that can truly fly. With over 1,400 species worldwide, these winged animals make up about 20% of all mammal types on Earth.

Their wings consist of thin skin stretched between long finger bones, quite different from bird wings.

These night flyers come in various sizes. The smallest, the bumblebee bat, weighs less than a penny. The largest, the flying fox, has a wingspan of up to 6 feet. Their fur colors range from light brown to nearly black, helping them stay hidden during daylight hours.

Bats live almost everywhere except the coldest spots on Earth. You’ll find them in forests, deserts, mountains, and even cities. Some stay in caves, while others hang from trees or hide in old buildings.

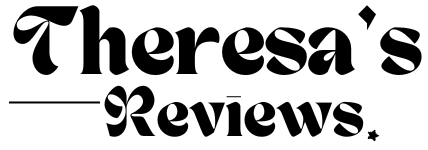

Most bats hunt at night using a skill called echolocation. They make high-pitched sounds that bounce off objects and return to their ears. This sound system lets them spot tiny insects in total darkness.

They can tell how big an object is, how far away it sits, and even how fast it moves – all without seeing it. This sound method works so well that bats can catch moths mid-flight and dodge obstacles smaller than a human hair.

The Life Cycle of a Bat From Tiny Pup to Night Flier

Mating Season

Bat mating happens once or twice yearly, often in fall or spring. Males attract females with special calls and scents. Some species form “harems” where one male mates with several females.

Others meet at gathering spots where males show off to win female attention. Most bat species don’t form lasting pairs but meet only to mate.

Pregnancy Stage

Female bats carry their young for 40 to 180 days, depending on the species. This time frame is quite long for such small mammals. Mother bats often gather in “maternity colonies” with hundreds or thousands of other pregnant females.

These groups offer safety and help maintain body heat. During pregnancy, females eat extra food to support their growing babies.

Birth and Early Days of a Bat

Most bats give birth to just one pup at a time. Baby bats (called pups) enter the world hairless with closed eyes and folded ears. Despite their small size, some weigh less than a penny- they make up about one-third of their mother’s weight.

Mothers catch their pups in their wing membranes during birth and then clean them right away.

Nursing and Growth

Mother bats feed their pups milk for 3 to 9 weeks. Young bats grow quickly, often doubling their birth weight within days. They cling to their mothers or to cave walls while mom hunts.

Around 3 weeks old, many pups start testing their wings with short flights inside their roosts. By 6 weeks, most can fly well enough to follow their mothers outside.

Learning to Hunt

Young bats must master flying and hunting before they can live on their own.

Mother bats often teach their pups how to find food and avoid dangers. Most young bats become independent within 1 to 2 months after birth.

Once on their own, they face the challenge of finding enough food and safe places to rest during the day.

Anatomy of an Aerial Acrobat

Bats have special body parts that make them perfect night flyers. Each feature helps them survive and hunt in the dark.

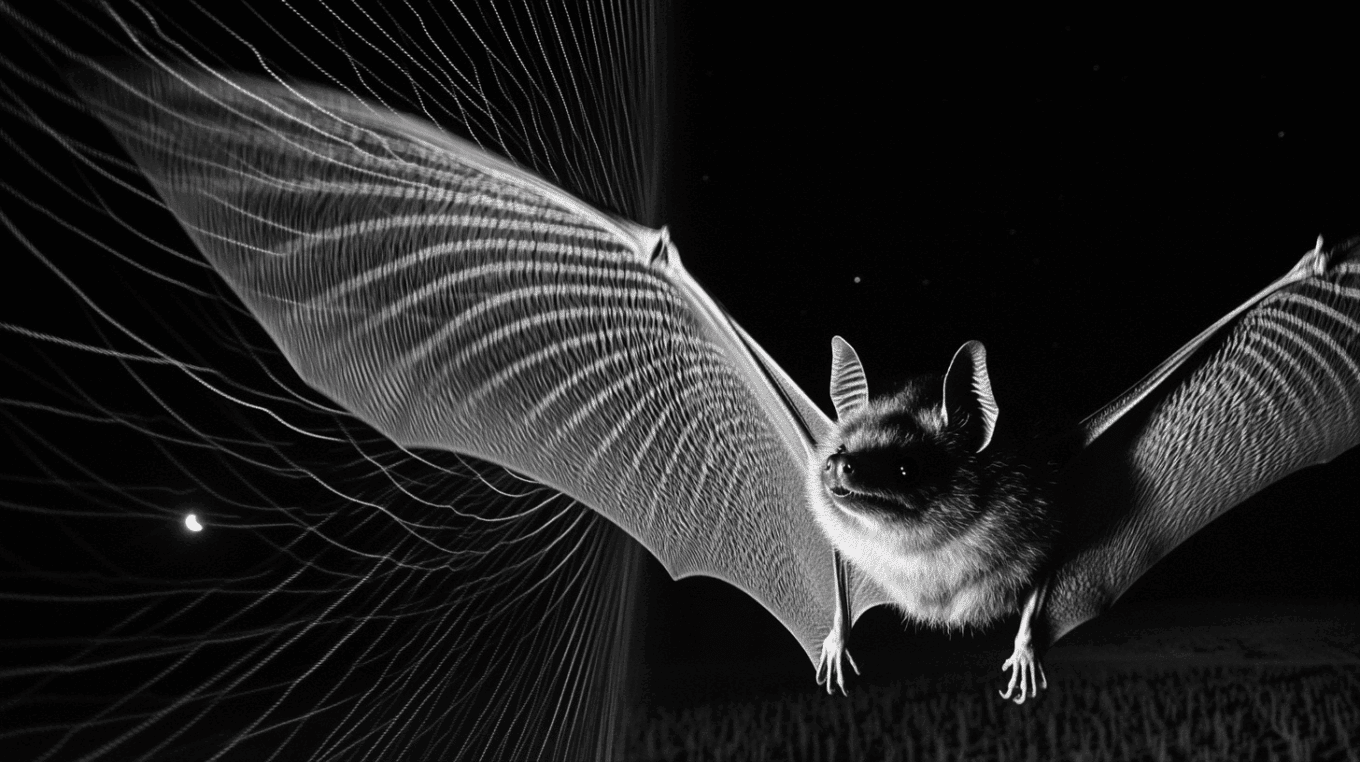

Bat Wing Design

- Wings consist of thin skin membranes (patagium) stretching between arms, legs, and tail.

- Long finger bones extend outward to support these wing membranes, unlike birds’ feathered wings.

- Small thumb claws protrude from wings to assist with climbing and grasping food.

Body Adaptations for Hanging

- Legs rotate outward to enable effortless upside-down positioning.

- Specialized tendons automatically lock feet in place during rest, preventing falls while sleeping.

Sensory Features

- Oversized ears capture sound waves for echolocation navigation – some species like long-eared bats have ears nearly matching their body length.

- Eye size and development vary by feeding habits.

These anatomical features develop throughout a bat’s growth to support their nighttime lifestyle and specific ecological needs.

Seasonal Behaviors of Bats Throughout a Year

Bats change their habits throughout the year to match the shifting seasons. They must adjust to find food, stay warm, and raise their young as weather patterns change.

The yearly cycle of a bat reflects a careful balance between using energy and saving it for tougher times. Bats adjust their habits year-round to survive changing conditions, balancing energy use with conservation needs.

Spring: Bats wake from hibernation as temperatures rise. Females form maternity colonies and begin hunting after months of inactivity.

Summer: Peak activity season with pup births and constant nighttime foraging. Young bats learn to fly and hunt while their mothers work overtime to feed them.

Fall: Mating season begins alongside intensive feeding to build fat reserves. Some species migrate south to warmer regions.

Winter: Hibernation in caves, mines, or buildings. Heart rate and body temperature drop dramatically as bats live off stored fat until spring.

This annual cycle ensures survival through resource scarcity and temperature extremes.

Different Types of Bats You Should Know About

Most people think all bats are the same – small, black, and scary. But the Bat-family is much more varied than that. With over 1,400 different kinds worldwide, bats come in many shapes, sizes, and colors. They also eat different foods and live in different places.

Here’s a look at the main groups of bats and what makes each unique.

| Bat Type | Diet | Size Range | Habitat | Notable Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Megabats (Fruit Bats) | Fruit, nectar, pollen | Medium to large (2-16 inches) | Tropical forests | Large eyes, good vision, fox-like faces |

| Microbats | Mostly insects | Small to medium (1-5 inches) | Worldwide | Complex echolocation, smaller eyes |

| Vampire Bats | Blood | Small (3-3.5 inches) | Central and South America | Heat sensors in nose, can walk and run |

| Fishing Bats | Fish, crustaceans | Medium (4-5 inches) | Near water bodies | Large feet with claws for catching fish |

| Nectar Bats | Flower nectar | Small to medium (2-3 inches) | Tropical regions | Long snouts and tongues for reaching nectar |

Threats and Conservation of Bats

Bats face many dangers today. Habitat loss tops the list as forests fall and caves get blocked. Wind turbines cause deaths when bats fly into the moving blades. Diseases like White-Nose Syndrome have killed millions of bats in North America alone.

People often fear bats due to myths and kill them on purpose. Climate change shifts food sources and roosting spots too quickly for bats to adapt. Yet help is coming.

Groups work to save these helpful creatures through:

- Building bat houses to create new homes

- Putting gates on caves that let bats in but keep people out

- Teaching folks about how bats help control pests and pollinate plants

- Creating “bat-friendly” wind farms that turn off during peak bat flying times

- Setting up protected areas where bats can live without human harm

These steps make a difference. When we protect bats, we also protect the many ways they help keep our world in balance.

Wrapping It Up

Now you know why bats matter more than most people think. These night flyers do much more than just hang upside down and look spooky.

The bat reminds us how special these animals truly are; from tiny, helpless pups to skilled hunters who clean our skies of insects every night.

Consider putting up a bat house in your yard. Or join a local bat watching event to see them in action. The life cycle of a bat reminds us that even small creatures play big roles in keeping our world in balance.